Graduate Students Present Research at American Chemical Society Conference

Office of Communications and Marketing

Young Hall

820 Chestnut Street

Jefferson City, MO 65101

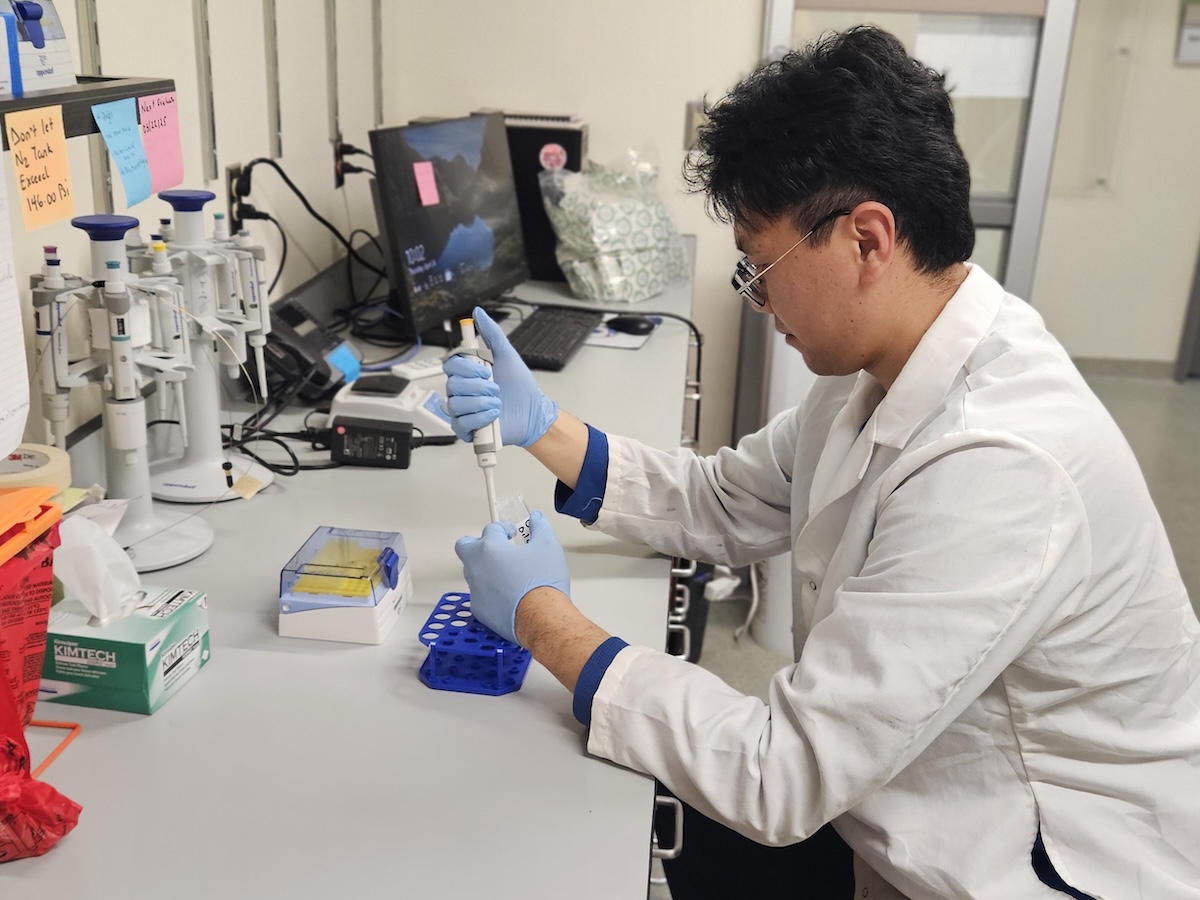

University of Missouri Ph.D. student Chao Ke uses chemistry equipment in his lab at Lincoln University’s Dickinson Research Center on April 24.

University of Missouri Ph.D. student Chao Ke uses chemistry equipment in his lab at Lincoln University’s Dickinson Research Center on April 24.

When you’re deep in a research project, it can feel like you’re working inside a box — focused and separate from the rest of the world. Conferences offer a chance to step outside that box, share your work with peers and learn from the discoveries of others.

Three researchers from Lincoln University of Missouri’s (LU) Dickinson Research Center traveled to San Diego, California, in March to expand their horizons at the 2025 Spring American Chemical Society Meeting.

Amrita Dhakal and Dipsana K.C. are LU graduate students, and Chao Ke is a University of Missouri Ph.D. student. The trio joined more than 10,000 other attendees in San Diego between March 21-27 to network, learn and present their research.

The conference featured career fairs, product expos, remarks from featured speakers and more. All three students presented orally, and Dhakal showcased a research poster as well. Presentations attracted groups of 20 or 30 people, with most attendees specializing in the subject matter.

Dhakal said presenting her research at the conference made her realize that research is not just about the work itself, but rather the ability to communicate ideas to the world. Sharing her work helped Dhakal realize she is part of something bigger than her individual project.

Lincoln University graduate students Dipsana K.C. and Amrita Dhakal stand in their lab at Dickinson Research Center on April 23.

Lincoln University graduate students Dipsana K.C. and Amrita Dhakal stand in their lab at Dickinson Research Center on April 23.

“Getting that exposure to the American Chemical Society, being able to present my work and receiving expert feedback — that was really helpful,” Dhakal said.

In addition to presenting their research, Dhakal, K.C. and Ke also listened to presentations from peers — some of whom focused on similar subjects. K.C. said this introduced her to new ideas and perspectives she can apply to her work.

“Attending this type of conference is really rewarding," K.C. said. "You receive feedback and communicate with peers — there’s so much room to grow. You are only thinking in a small box when you’re doing your research, but when you meet other people doing their own work, you start thinking of new directions you can go in.”

She added that it was nerve-wracking to present to a large group of strangers, but it helped build her confidence and improve her communication skills.

For Ke, the conference served as an opportunity to present findings from research he has worked on for two or three years. In addition to his eagerness to share his work, he said the conference helped him prepare to defend his thesis.

He said meeting researchers in similar areas of study gave him innovative ideas, and watching others present helped him improve his presentation skills.

“It motivated me to do better in the future,” Ke said. “It was a good opportunity to improve myself.”

Ke presented research exploring parasite control in small ruminants, like sheep and goats, using natural plant compounds. Specifically, he looked at controlling gastrointestinal nematodes, also known as worms.

His project involved extracting chemicals from different plants and observing how they affected nematodes. Then, among effective plants, he determined which chemicals kill those worms the best.

University of Missouri Ph.D. student Chao Ke stands in his workspace at Lincoln University’s Dickinson Research Center on April 24.

University of Missouri Ph.D. student Chao Ke stands in his workspace at Lincoln University’s Dickinson Research Center on April 24.

He’s also studying which genes make animals more naturally resistant to parasites. The goal is to support more effective and alternative treatment options. Ke said his findings could help organic farm owners establish anti-parasitic pastures for grazing animals, eliminating the need for parasiticides. It could also support breeding parasite-resistant livestock.

K.C.’s research looked at the impact of agricultural nanoparticles — extremely small particles used in fertilizers, pesticides and other farming products — on soil microbes. These microbes are tiny living organisms, such as bacteria and fungi, that live in soil and break down organic matter, circulate nutrients and help plants grow.

As nanoparticle use in agriculture continues to rise, K.C. said there is still much to learn about their impacts on soil environments and the crops that depend on them.

“Many nanoparticles are helpful in some way, but at certain concentrations and with certain uses, they might have negative impacts,” K.C. said.

Once complete, she said her research could help determine which nanoparticles are more toxic to microbes and what concentration of nanoparticles crosses the line between helpful and harmful. She said those revelations could ultimately inform farmers on what concentration they should use in their soil.

Dhakal’s research sought to explore how PFAS chemicals — sometimes referred to as "Forever Chemicals" — enter plant systems and how they affect those systems. PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are manmade chemicals used in everything from cookware to furniture.

“PFAS has been used for decades because of its high strength, but now it’s become a problem because it’s everywhere," Dhakal said. "It has really strong chemical bonds, so it can’t be broken."

PFAS chemicals have been used so widely and for so long that they’re found in water, soil, animals and even human bloodstreams. Using mung bean sprouts, a legume primarily grown in Asia, Dhakal studied how PFAS is absorbed and the effects it has on plants’ roots, stems and leaves.

Her research, once finished, could help determine ways to limit human exposure to PFAS — that could mean using alternative chemicals or finding new agricultural methods.

Lincoln University graduate students Amrita Dhakal and Dipsana K.C. equip protective equipment in their workspace at Dickinson Research Center on April 23.

Lincoln University graduate students Amrita Dhakal and Dipsana K.C. equip protective equipment in their workspace at Dickinson Research Center on April 23.

These projects all seek to help farmers and their communities, whether that’s finding natural treatment options for parasites in livestock or reducing the amount of toxic chemicals in soil and crops.

Dhakal, K.C. and Ke’s research, supported by their supervisors and colleagues at Dickinson Research Center, represents Lincoln’s mission to serve Missouri’s agricultural community. They’ve made great strides in their work, and there’s much more to explore.

And thanks to the American Chemical Society Meeting, the trio discovered new perspectives for viewing their research and gained valuable communication skills to help share that work with the world.

Dhakal is advised by Dr. Qingbo Yang, and her work is supported by his USDA-NIFA Evans-Allen project. K.C. and Ke are advised by Dr. Tumen Wuliji. K.C.’s work is a part of Dr. John Yang’s NSF-funded research, and Ke’s project is funded by Wuliji’s CBG project.